What’s really on trial in Kenosha and Glynn County?

Last week, Kyle Rittenhouse pulled a Brett Kavanaugh and ugly cried on the witness stand in a desperate plea for sympathy. His made-for-Twitter hysterics were meant to appeal to an audience that could paint him as “just a boy” … a boy who killed a man in a state he doesn’t live in with a gun he shouldn’t have had.

Meanwhile, in Georgia, the defense attorneys for the killers of Ahmaud Arbery, the young Black man who was lynched by three white vigilantes, are defending their killing of an innocent jogger as a matter of a “citizen’s arrest” gone wrong.

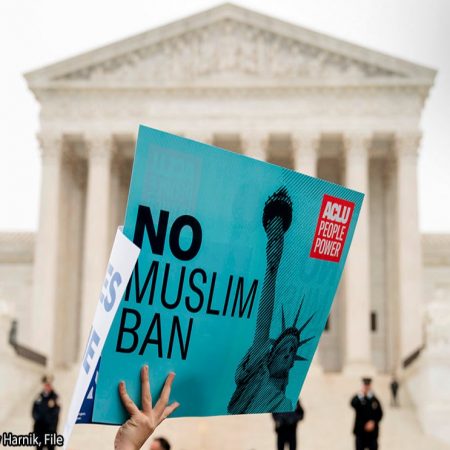

In split screen, these trials offer us the opportunity to zoom out and examine the world in which both of these cases rise. On their face, both consider what limits — if any — our society is willing to put on lethal white vigilantism, when, where, and for what purpose white people are allowed to kill after taking the law into their own hands.

Go a little deeper, and you realize these cases also hinge on when and where unarmed Black people are allowed to go at all. After all, Ahmaud Arbery’s killers took up arms to hunt down an unarmed Black man taking a jog through their neighborhood. Kyle Rittenhouse brought his AR-15 across state lines in response to unarmed, mainly Black protestors. Kevin Gough, defense attorney for Arbery’s killers made this point himself when he tried to call for a mistrial simply because Black civil rights leaders showed up to the courtroom:

Peacefully protesting a police shooting, jogging in a neighborhood … even sitting in a courtroom — none of these are explicitly threatening. And yet all of them have been deemed threatening by particular white folks if the person who is doing them is Black. In that case, you can add them to other threatening behaviors, like bird watching in Central Park or sipping coffee at Starbucks.

On trial in Kenosha, Wis. and Glynn County, Ga. is the deadly narrative that Black people are dangerous, that their very existence in public space is threatening. When Kyle Rittenhouse performed his histrionics on live TV, he was reenacting a classic American script, appealing to a racist narrative that goes deep. Like Amy Cooper and every other Karen before or since, he knows that by playing the threatened white person, he could literally get away with murder. Indeed, that’s the same argument Ahmaud Arbery’s killers are trying to make: the sight of a Black man jogging in the neighborhood is enough of a threat to meet up with your buddies, arm yourself, and confront him … and ultimately shoot and kill him.

And that’s what makes the case of these trials, themselves, so frustrating. We are nowhere near a conversation about why some white folks find the very presence of Black folks so threatening. Instead, we’re having a conversation about whether or not they’re allowed to kill them over it.

Even if the juries convict both Rittenhouse and Arbery’s killers, all these juries can do is establish the lowest possible floor. After all, there’s a long way between not being murdered and being free. As long as we fail to deal with the racist narrative that renders Black people a threat, Black folks remain at risk of being murdered — whether by vigilantes cosplaying as cops, or by cops themselves. Those whom it does not kill, it robs of their basic freedom.

To make things worse: as obvious as either of these cases should be, it’s nowhere near certain that juries will make the just decision. It’s too easy to find particular excuses for general truths. If the juries exonerate one or all of these vigilantes, they will, by definition, have to endorse the logic that the killer was acting in self-defense—that, by implication, unarmed Black people are a threat that demands deadly force.

We often numb our racist history in this country with the salve that however unjust, inequitable, or wrong we have been, we are yet moving forward. But these trials offer no steps forward. The fact that we are still litigating these questions is, itself, a step back.

2021

1,575 views

views

0

comments